Article: Fundamentals of Modeling Inventory Locations Using Microsoft Dynamics AX

Editor’s Note: The following article is drawn from Dr. Hamilton’s new book about Supply Chain Management using Microsoft Dynamics AX. The book focuses on supply chain management in manufacturing and distribution businesses, and covers the software capabilities within the new Dynamics AX as well as AX 2012 R3.

The definition of physical sites containing inventory represents a key part of modeling any supply chain in manufacturing and distribution. The fundamental options for modeling these physical sites in Microsoft Dynamics AX involve the use of AX sites and AX warehouses within a legal entity. In this article, we will use the generic term of physical site or inventory location for conceptual explanations, and the terms “AX site” and “AX warehouse” when explaining system-specific functionality. In addition, we will use the term bin location when referring to the locations within an AX warehouse. The model of inventory locations has multiple impacts. It impacts the definition of items, bills of material (or formulas), resources, routings, product costs, coverage planning data and S&OP game plans. It impacts the business processes related to inventory, such as sales orders, purchase orders, transfer orders, production orders and quality orders. The article starts with the major variations of modeling inventory locations within one or more legal entities, and then covers the unique considerations about using AX sites and AX warehouses. After defining this information within AX, you can view a graphical portrayal of the inventory locations in a multi-level structure termed the operations infrastructure. The article concludes with a case study illustrating some of the considerations about using AX sites and warehouses.

1. Major Variations for Modeling Inventory Locations

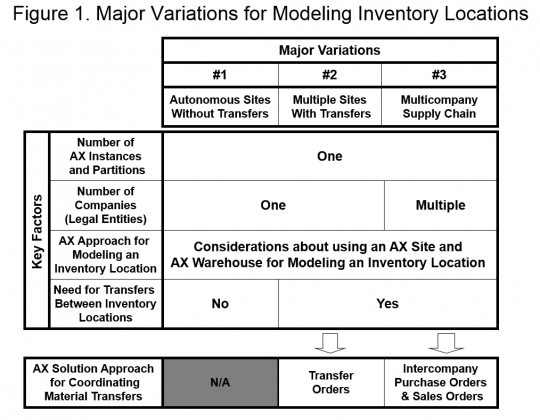

The wide variety of scenarios for supply chain management in manufacturing and distribution can be distilled into a few major variations for modeling inventory locations within AX.[1] Several key factors differentiate the nature of these variations, such as the number of AX instances, the number of legal entities related to the inventory locations, and the AX approach for modeling an inventory location. Another key factor involves the need for transfers between inventory locations and the solution approach for coordinating transfers. The most common variations and the key factors are summarized in Figure 1 and described below.

The simplest variation consists of a single AX instance and partition, and a single legal entity with one or more inventory locations. The locations may reflect autonomous sites without transfers, or they may reflect a distribution network with transfers between locations. The source warehouse for a planned transfer order can be defined as part of coverage planning data for an item and destination warehouse.

Transfers between locations in a multicompany supply chain represent a more complex variation. Transfers can be coordinated by intercompany purchase orders and sales orders, and by master scheduling logic that generates planned intercompany demand. All of these variations involve several considerations about using AX sites and AX warehouses for modeling inventory locations. As one consideration, you can specify whether site-specific or warehouse-specific pricing (or companywide pricing) should apply to an item’s sales prices or purchase prices. You define these policies within the Storage Dimension Group assigned to the item. Some unique considerations only apply to an AX site or an AX warehouse, as described in the next two sections. Several additional variations represent less common scenarios and are not included in Figure 1. For example, a given enterprise may employ two or more AX instances, where intercompany trade between locations in each instance can be handled by the Data Import/Export capabilities within AX.[2] The same capabilities also apply to intercompany trade when one of the companies employs a different ERP system than AX. A single instance can also be partitioned with one or more companies in a partition, thereby isolating the information as if separate instances were being used. Further explanation of these additional variations falls outside the scope of the article

The simplest variation consists of a single AX instance and partition, and a single legal entity with one or more inventory locations. The locations may reflect autonomous sites without transfers, or they may reflect a distribution network with transfers between locations. The source warehouse for a planned transfer order can be defined as part of coverage planning data for an item and destination warehouse.

Transfers between locations in a multicompany supply chain represent a more complex variation. Transfers can be coordinated by intercompany purchase orders and sales orders, and by master scheduling logic that generates planned intercompany demand. All of these variations involve several considerations about using AX sites and AX warehouses for modeling inventory locations. As one consideration, you can specify whether site-specific or warehouse-specific pricing (or companywide pricing) should apply to an item’s sales prices or purchase prices. You define these policies within the Storage Dimension Group assigned to the item. Some unique considerations only apply to an AX site or an AX warehouse, as described in the next two sections. Several additional variations represent less common scenarios and are not included in Figure 1. For example, a given enterprise may employ two or more AX instances, where intercompany trade between locations in each instance can be handled by the Data Import/Export capabilities within AX.[2] The same capabilities also apply to intercompany trade when one of the companies employs a different ERP system than AX. A single instance can also be partitioned with one or more companies in a partition, thereby isolating the information as if separate instances were being used. Further explanation of these additional variations falls outside the scope of the article.

2. Unique Considerations of Using AX Sites

Each physical site is typically modeled as an AX site with one or more AX warehouses. An AX site has several unique aspects that are not applicable to an AX warehouse, as summarized below.

Financial Reporting by AX Site Each AX site can have an associated value for a “site” financial dimension, thereby supporting profit and loss statements by site. This approach involves some setup information about the relevant financial dimension on the Dimension Link form, such as the financial dimension for department. The possible values for department must be defined (one for each site) and the applicable value must be assigned to each site. At that point in time, you can activate the financial dimension link.

Site-Specific BOM/Formula and Routing Information for a Manufactured Item The BOM/Formula and routing information for manufactured items can vary by AX site.

Site-Specific Standard Costs for an Item The assignment of an item’s standard cost can vary by AX site, especially when standard costing applies to the item. Stated another way, each material item must have an item cost record for each site with inventory. As a special case, an item may be assigned a zero value for its standard cost at a given AX site.

Site-Specific Labor Rates and Overhead Rates Labor rates and overhead costs can vary by AX site in manufacturing scenarios.

Site-Specific Policies for Quality Orders The automatic generation of quality orders within a business process – such as production or purchase receiving – provides a key tool for quality management. These policies can be site-specific or company-wide.

Other Production Data Related to an AX Site An AX site is assigned to a resource group and its related resources, so that the resources within the group are assumed to be in close proximity to each other. An AX site is also assigned to a production unit, which can determine the warehouse source of components for producing an item.

Order Entry Deadlines for an AX Site The definition of order entry deadlines only applies to an AX site. An order entry deadline frequently represents a prerequisite for meeting the departure time of a shipping vehicle, so that adequate time is available for picking/shipping activities. An order entry deadline also means that an order entered after the specified time will be treated as if it were entered the next day, thereby affecting the assignment of a promised ship date. You define a set of deadlines for each day within a week (termed an order entry deadline group), and then assign the deadline group to each customer and site.

Some Limitations Related to Manufactured Items One limitation applies to manufacturing scenarios with a product structure that spans more than one AX site. More specifically, the warehouse source for a manufactured item’s components and the destination warehouse for the item’s production order must be within the same AX site. When a product structure spans two AX sites, for example, this limitation often means that an item stocked or produced at one AX site must be transferred to a warehouse within a different AX site in order to use it as a component.

The same limitation applies to the standard cost calculations and inquiries for a manufactured item, since these can only span a single AX site. In order to avoid this limitation, some scenarios will use multiple AX warehouses within a single AX site to model different inventory locations.

3. Unique Considerations about using AX Warehouses

Each physical site is typically modeled as an AX site with one or more AX warehouses, as noted in the previous section. The assignment of an AX warehouse to an AX site cannot be changed after posting inventory transactions for the warehouse, so that the initial assignments must be carefully considered. Several unique aspects apply to AX warehouses.

Use of the Basic versus Advanced Approach to Warehouse Management The choice of a warehouse management approach can be warehouse-specific. In summary, a warehouse-specific policy about “use warehouse management processes” works in conjunction with a similar item-related policy to determine whether the basic or advanced approach to warehouse management will be used. The two different approaches have different conceptual models for managing inventory. Examples of these differences include the definition of bin locations within a warehouse, the use of reservation logic, and the impact on business processes involving inventory such as sales orders, purchase orders, transfer orders and production orders. A previous article explained these major options for warehouse management.

Warehouse Source of Components for a Manufactured Item The warehouse source of components can be defined in several different ways based on BOM/Formula and routing information for a manufactured item,. A component’s warehouse source indicates where to pick the item for a production order. For example, the picking location can reflect the scheduled resource (or resource group) for a routing operation, where the required components have been assigned the operation number.

The warehouse source must reflect the previously-mentioned limitation about a product structure than spans more than one AX site. This consideration is especially important in scenarios with subcontracted production, as described in a previous article.

Significance of a Transit Warehouse The need for a transit warehouse only applies when using transfer orders, and it supports tracking of in-transit inventory. You designate a transit warehouse when creating it, and assign a transit warehouse to each ship-from warehouse. One transit warehouse can be applicable to all ship-from warehouses within a given AX site, or you can define and assign a separate transit warehouse for each ship-from warehouse.

The concept of warehouse levels applies to the use of transfer orders, where you can identify a source warehouse for a given destination warehouse. In a simple example, the system will automatically assign a Level 0 to the source warehouse, Level 1 to the transit warehouse, and Level 2 to the destination warehouse. Master scheduling logic calculates item requirements at the destination warehouse and generates planned transfer orders from the assigned source warehouse.

Significance of a Quarantine Warehouse The need for a quarantine warehouse only applies when using the Basic Inventory approach to warehouse management, and when using quarantine orders for reporting inspection.

Significance of Using a Warehouse to Identify a Store in Retail Scenarios When you identify a warehouse as a store, Dynamics AX can support several additional capabilities for retail scenarios. At its simplest, it supports the use of call center capabilities for entering sales orders. Other retail-oriented capabilities – such as rules about a replenishment priority for the store (aka replenishment hierarchy) – fall outside the scope of the article.

4. Case Study: Modeling Inventory Locations

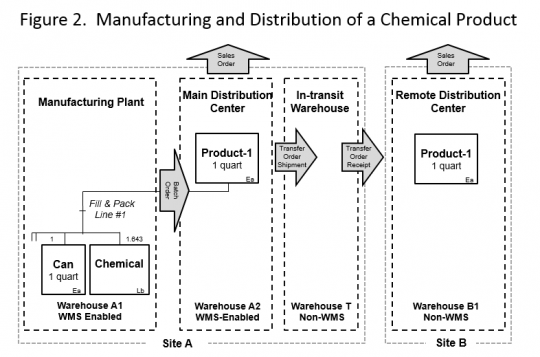

Several aspects of modeling inventory locations can be illustrated via a case study. In this scenario, a process manufacturing company purchased a chemical, packaged it in different container sizes, and sold it to different retail chains. The manufacturing and distribution of one product – a one quart container of the chemical — is illustrated in Figure 2 and described below. The figure indicates different AX sites and warehouses involved in the manufacturing and distribution of the product, and the arrows identify key inventory transactions.

The example product – identified as “Product-1” in the figure – could be produced on one of several “fill & pack” lines within the manufacturing plant. As shown in the figure, the manufacturing plant was identified as Warehouse A1 (within Site A), and the warehouse was designated as WMS-enabled in order to support advanced warehouse management capabilities. The key ingredients included the chemical and a 1 quart can. The scheduling logic within AX identified the appropriate fill & pack line, and this scheduled resource determined the appropriate production input location for delivering components via raw material picking work orders. Actual consumption was reported using the production picking list journal.

The finished quantities were received into an adjacent building that represented the main distribution center, and the palletized inventory was then put away into a stocking location. As shown in the figure, the main distribution center was identified as Warehouse A2 (within Site A), and the warehouse was designated as WMS-enabled. The finished product was primarily sold from the main distribution center.

A proportion of the product was transferred to and sold from a small remote distribution center. As shown in the figure, the remote distribution center was identified as Warehouse B1 (within Site B), and the warehouse was designated as a non-WMS warehouse in order to support the basic warehouse management capabilities. The in-transit inventory was updated by the transfer order shipment and receipt. The item’s standard cost was slightly higher at Site B to reflect the additional shipping costs, and the cost change variance was recognized after reporting the transfer order receipt.

5. Concluding Remarks

The definition of inventory locations represents a key part of modeling any supply chain, and there are several fundamental options for modeling these locations within AX. These options include the use of AX sites and AX warehouses to model inventory locations, and use of the basic versus advanced approach to warehouse management at a given AX warehouse. This article reviewed the major variations for modeling inventory locations, highlighted several considerations about using AX sites and AX warehouses, and included a case study to illustrate some of these considerations.

[1] The analysis does not cover retail-oriented operations where stores can be modeled as an AX warehouse, although it is mentioned briefly.

[2] The Data Import/Export framework within the New Dynamics AX replaces the Application Integration Framework (AIF) capabilities in previous AX versions such as AX 2012 R3.

Source:MSDynamicsWorld.com